Published 2021/09/22

The magic behind

the original king kong

From Willis O’Brien to Isabel Garrett, we look at

some of the pioneering stop motion animators

Words by Oliver Trace

“Oh, no, it wasn’t the airplanes. It was beauty killed the beast.”

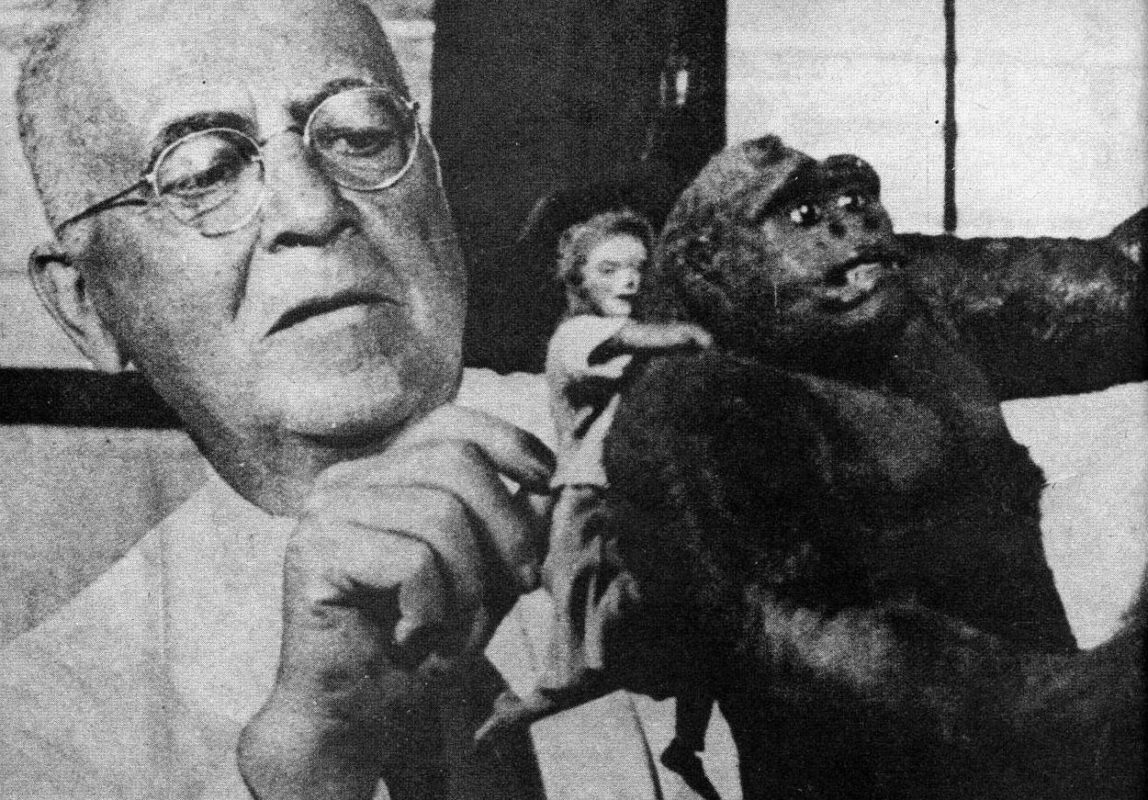

King Kong is a classic. Multiple remakes. Millions at the box office. It doesn’t go out of fashion. When the words are uttered, King Kong, the film that readily comes to mind for a younger audience is the one directed by Peter Jackson in 2005. In that movie, the gorilla, King Kong, is brought to life through CGI: computer generated imagery. But the original gorilla in the 1933 version is a product of stop motion animation. Pioneering animator and artist Willis O’Brien (1886 – 1962) was one of the first to create realistic miniature puppets, photographed frame by frame, and combine them with live action footage. The result had cinema-trippers leaving in awe.

Willis O’Brien, working on miniatures for King Kong

The Lost World (1925) and Mighty Joe Young (1949), the second of which picked up the Academy Award for Best Visual Effects in 1950. His assistant on that movie was Raymond Harryhausen (1920 – 2013), Willis’ protégé. It is through Raymond that Willis has had the biggest impact on the headliner movie-makers that we all know and love today. Steven Spielberg, Peter Jackson, Tim Burton, James Cameron, and many more, all cite Raymond Harryhausen as an influence on their movies. He was head of visual effects on the epics Jason and the Argonaughts (1963) and Clash of the Titans (1981).

Tipsy Flamingo, Isabel Garrett, 2021

One contemporary artist who continues to experiment with a combination of live action and stop motion is Isabel Garrett. She may ring a bell, as she has created some of our most popular cards, including Tipsy Flamingo and Head in the Sand. Her characters are stylised puppets, they do not aspire to be realistic miniatures, the approach Willis took to creating King Kong in 1933. Isabel builds her characters with felt, which gives them an especially tangible, approachable nature. They jump out visually against the crispness of the live action world in which they are situated.

Listen to me Sing (2019), Isabel Garrett

Isabel’s scenes have a freshness and vibrancy that was out of reach to artists experimenting with stop motion in the 1930s, when everything had to be done in black and white. It’s a fine example of how technology is tied to art: the frontier of one is where we tend to find the frontier of the other. It’s likely Willis would be proud to see how far the craft has come since his initial steps into the unknown. Ninety years on, Isabel brings a new voice to the table. Her most recent film, ‘Listen to me Sing’, won Best Animation at the BAFTA qualifying Underwire Festival. Her sense for a comic moment combined with a refined and balanced aesthetic make her one to watch in the years to come.